Organ and Tissue Donation Conference

With a mere 19,000 registered donors in Lebanon, there is a dire need for many more to save lives.

Organ donation may be one of the easiest ways to save a life. Yet in Lebanon, many do not readily register as organ or tissue donors for cultural and religious reasons.

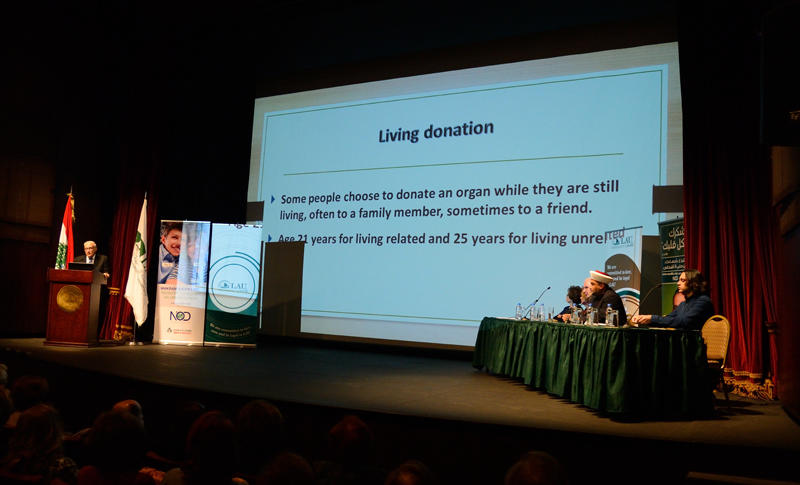

That is why the President’s Circle at LAU recently held a conference in collaboration with the National Organization for Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation (NOD) highlighting the humanitarian side of the issue and the dire need for more donors.

Introduced by LAU alumna and former Director General at the Ministry of Social Affairs Nimat Kanaan (BA ’58), LAU President Joseph G. Jabbra went on to thank the President’s Circle for convening on a topic that holds “profound humanitarian significance.”

A panel discussion moderated by NOD Coordinator Farida Younan followed with a testimony by a donor family, and an explanation of the clinical aspects of donation by neurologist Dr. Kamal Kallab.

Because there is no universal family law in Lebanon, matters having to do with topics like organ donation are settled by the country’s religious institutions. Presenting the Christian view on the subject, Father Louis Khawand stressed that the Church endorses organ and tissue transplants from live donors provided they do not lead to death or disability for the donor. The Church also supports organ transplants from animals, he said, as long as they do not in any way “alter the human identity.”

Khawand expressed regret that “so many organs are consigned to the earth” when they could benefit someone in need. “Our bodies are not our possession, but God’s gift,” he added, a view shared by Sheikh Bilal Muhammad al-Malla of Dar al-Fatwa.

For his part, al-Malla pointed out that the “jurisprudential fatwa councils in the Arab and Islamic world, and contemporary scholars, agree on the permissibility of organ and tissue transplants and donations, within the legal, professional and religious perimeters that protect the living or deceased person’s sanctity and dignity, and preserve the genealogy that entails rights, duties, obligations and inheritance.” Both religious figures, however, insisted that deceased donors have to be certified “clinically dead” before any organs are removed. They also warned against the exploitation of organ donation for commercial purposes. Al-Malla stressed that the sale of organs and organ trafficking are forbidden in Islam and are considered “a crime against a person’s dignity and sanctity.”

On that score, nephrologist Dr. Antoine Stephan, and co-founder of Lebanon’s National Organization for Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation (NOOTDT), pointed out that organ trafficking was no longer a problem in Lebanon thanks to the vigilance of the Ministry of Health.

In his talk, Stephan emphasized the importance of donation in saving or improving the quality of a person’s life. Everyone, at one point or another, he noted, might need an organ, of which there is a great worldwide shortage that could be reduced by more people registering as donors.

With a mere 19,000 donors on Lebanon’s official list, Stephan called for amending the 1983 Lebanese law sanctioning organ donation for scientific purposes. NOOTDT, he pointed out, covers all expenses incurred by organ and tissue donations, and only requires the donor family’s consent. Donations, he said, are subject to medical laws of confidentiality, and organ removal in no way causes disfigurement or scarring of deceased donors.

Speaking of his experience as a liver recipient at the end of the session, AUB student Ahmad Anouti said that the whole process was not without complications; but it did, ultimately, give him his life back.