Japanese Praemium Imperiale Award for Alumna Mona Hatoum

Renowned artist Mona Hatoum is named laureate of the 2019 Praemium Imperiale Award for her lifetime achievement in sculpture.

Artist and Alumna Mona Hatoum recently received the prestigious Japanese Praemium Imperiale Award, dubbed the Nobel Prize of Arts, for her lifetime achievement in sculpture. She was presented with the award by Prince Hitachi, honorary patron of the Japan Art Association, in a ceremony held in Tokyo in October.

Hatoum was one of five international artists, said laureates, recognized for the impact they have had internationally on the arts, and for their role in enriching the global community.

“I am very honored to have been included amongst all the great recipients of this award past and present,” Hatoum said. “It’s a truly momentous experience.”

This is the latest in a raft of accolades that Hatoum has garnered over her 40-some-year career, that have included the Art Icon 2018, London, the Trobades Albert Camus Award, Spain, the Ruth Baumgarte Award, Germany, the Hiroshima Art Prize, Japan, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Medal Award, Boston, the Joan Miró Prize, Barcelona and the Käthe-Kollwitz-Preis 2010, Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

A British Palestinian born in Beirut, Hatoum (‘72) studied fine arts at Beirut University College, as LAU was known back then. A visit to London in 1975 turned into a permanent stay for Hatoum when the civil war broke out in Lebanon. Fulfilling her love for the arts, she went on to train at both the Byam Shaw School of Art and the Slade School of Fine Art, University College, London.

In her long artistic career that incorporated installations, videos, sculpture, and photography, Hatoum’s work has won great acclaim worldwide. She has held solo exhibitions at Centre Pompidou (Paris), Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), The New Museum of Contemporary Art (New York), Tate Modern (London), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Sydney), and the Guggenheim Museum (New York and Bilbao, Spain) among many others.

She has also participated in a number of recognized group exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale (1995 and 2005), Documenta, Kassel (2002 and 2017), Biennale of Sydney (2006), Istanbul Biennial (1995 and 2011) and Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art (2013).

Hatoum’s accomplishments did not go unnoticed by LAU’s Alumni Relations Office who granted her the Alumni Achievement Award in 2016.

The world that Hatoum conveys through her sculptures is precarious and threatening, colored by trauma – a “Terra Infirma,” and a Hot Spot fraught with conflict. In the large installations, Map, 1999, and Map (clear), 2015, her world map is a mass of glass marbles, dazzling yet unstable.

“I work with feelings of displacement, disorientation, estrangement – when the familiar turns into something foreign or even threatening,” Hatoum says. “It’s about shattering the familiar to create uncertainty and make you question things that you normally take for granted.”

Trauma, she believes, alters our view of the world around us, transforming a familiar situation into a source of dread and anxiety. “I’m really interested in this concept of the uncanny, which is a Freudian concept,” she explains. “It’s called unheimlich, which means unhomely, and basically it’s about everyday objects that suddenly become unfamiliar or even threatening because they have been affected by some kind of trauma.”

Hatoum became well-known in the 1980s for a series of performances and videos that focused on the body, before she moved on to large-scale sculptures and installations, choosing her material according to the space she was going to exhibit in: marbles, mesh, steel cages and even human hair.

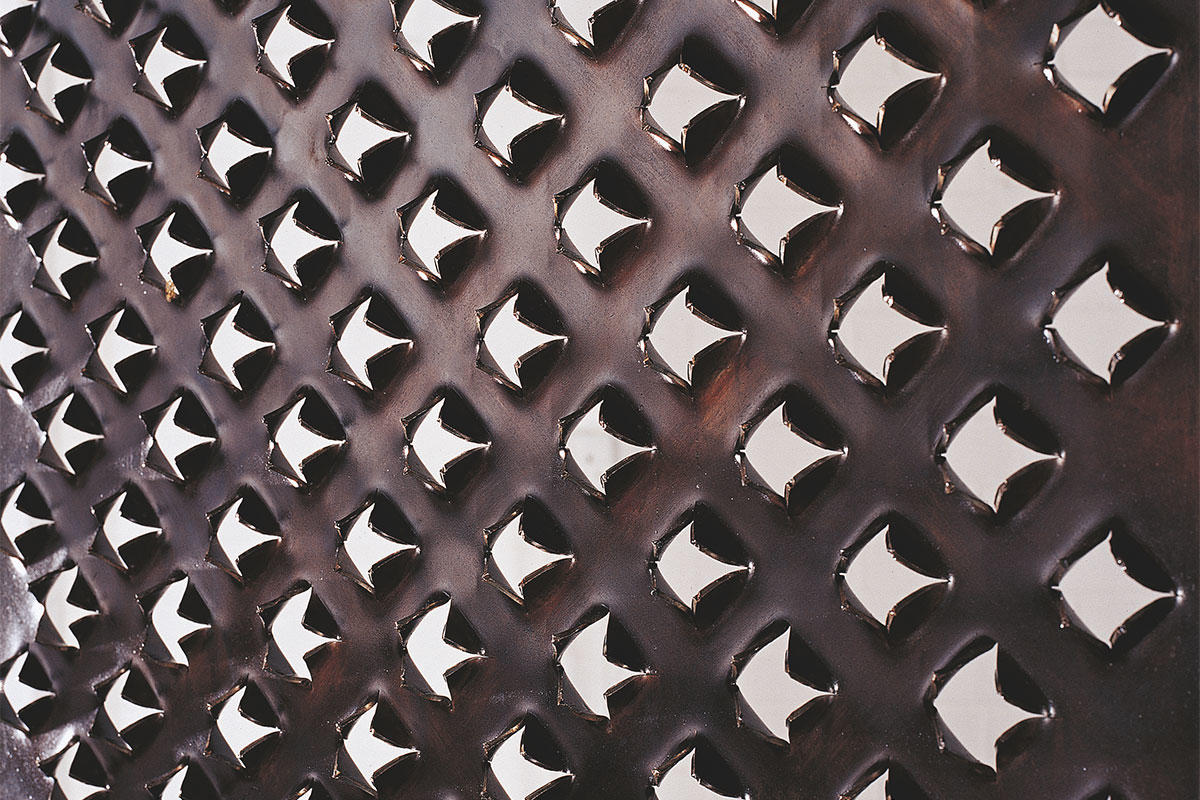

Her large-scale installations are jolting to the viewer, at once “seductive and dangerous, attractive and repulsive.” Ordinary kitchen utensils take on a sinister meaning: a life-size cheese grater acts as a screen, a paravent, in Grater Divide, 2002, and the food mill in La Grande Broyeuse (Mouli-Julienne x 17), 1999, is large enough to slice up a human being. In Homebound, 2000, a scene staged with familiar domestic items – furniture and kitchen utensils – on closer inspection reveals an electrified, chilling reality of a home that has become lethal. Threat is also present in Nature morte aux grenades, 2006-2007, where colorful crystal objects turn out to be made in the shape of hand grenades.

This sense of foreboding is amplified in sculptures that focus on surveillance. In Corps étranger, 1994, where the artist’s internal organs are displayed through a video projection of an endoscopy, the body itself becomes “fascinating and disgusting,” where no part escapes scrutiny.

While uncertainty may be alarming in Hatoum’s work, it is a driving force in her professional life. “The most exciting thing about being an artist, for me,” she admits, “is that I never know where the next exhibition is going to take me to in the world, and what I will end up making, and I find this very exciting – that not knowing.”