What Do We Know About Monkeypox?

Dr. Jacques Mokhbat distills available scientific information on monkeypox and dismisses its likelihood of becoming another pandemic.

No sooner had the panic surrounding COVID-19 subsided than fears about the monkeypox virus started spreading worldwide. According to the WHO, 12 Member States – where the disease is non endemic – have reported cases of monkeypox since May 13, 2022, but no fatalities.

In Lebanon, says LAU Chair of the Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases Jacques Mokhbat, there have been no suspected or confirmed cases. Furthermore, adds Dr. Mokhbat, while the WHO is on the lookout, it has not raised the level of the disease to an epidemic.

In this interview, Dr. Mokhbat sets the record straight about the outbreak and what to expect.

Why is the disease called monkeypox?

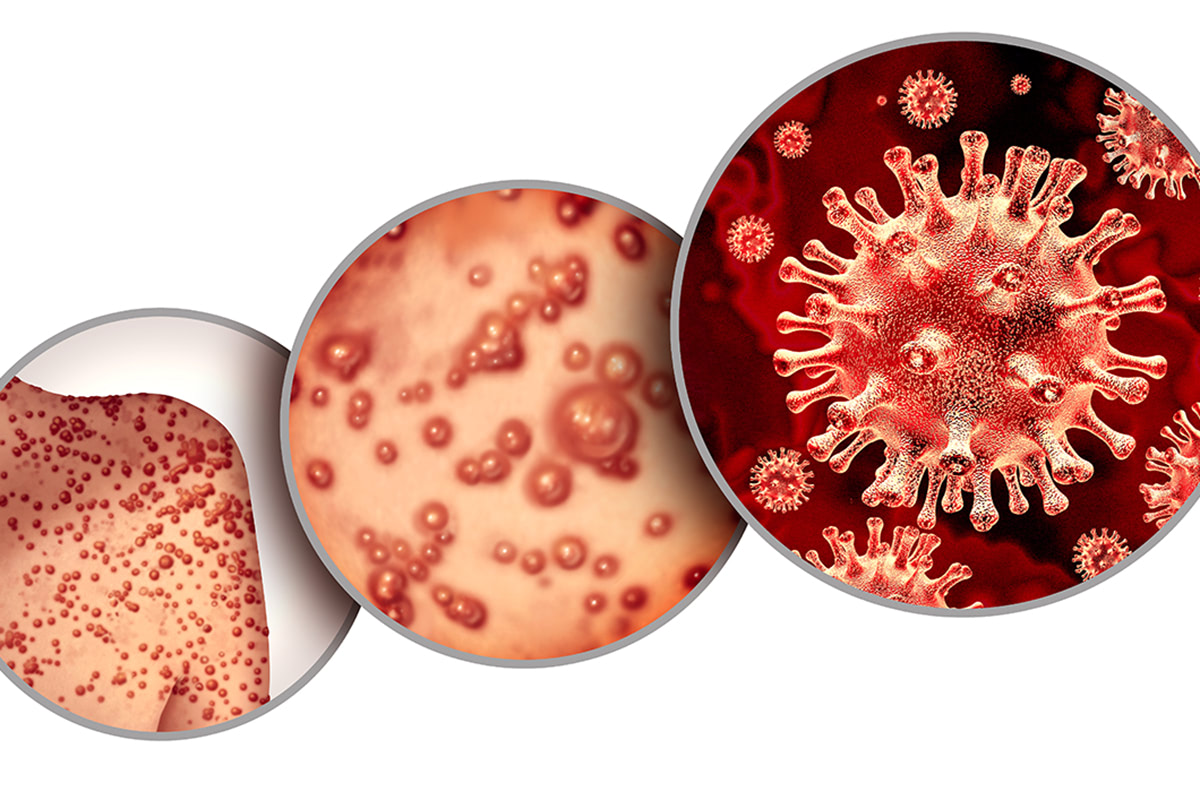

It was first detected in the 1950s in a monkey that was in captivity as a pox-like disease, which is characterized by a pustular rash, a rash with pus. So, it was similar to smallpox, a disease known in humans for generations, ever since antiquity. When they saw that it differed somewhat from the traditional pox, they called it monkeypox. But it probably originated in rodents and spread to monkeys and occasionally humans.

When was it first detected in humans?

The first case of monkeypox in humans was in the 1970s and ever since it has reappeared on a yearly basis. The majority of cases were in Central Africa, where the disease is endemic, in the rainforest. The more we invade nature and destroy animal habitats, the higher the risk of us acquiring diseases from animal species.

Also, fears at the outbreak of smallpox before the 70s had led to a huge campaign to vaccinate from birth, which stopped in the mid-70s. The last case of smallpox was reported in Somalia in 1977. By 1972, or others say 1977, as the world was considered free of smallpox, no one got vaccinated. What has happened is that an increasing number of people have become prone and more susceptible to catching smallpox, or as is the case, monkeypox.

Smallpox, incidentally, should not be confused with chickenpox, which is a totally different type of virus that occurs in children and that is not fatal.

First it was SARS-CoV-2 and now the monkeypox virus. Why have we been witnessing an emergence or spread of new viruses?

There are two main reasons for this: our invasion of nature and international travel, which also includes the transport of monkeys and other animals, such as rodents.

Firstly, we are destroying the equilibrium in mother nature. Don’t forget that trees are supposed to protect the normal flora and fauna, animal species that are supposed to get rid of fleas and insects. Now we are paying the price for our destruction of the ecosystem. We are going to become dominated by mosquitoes, fleas, rodents and viruses that originate with rodents.

Secondly, viruses are more likely to spread with people’s increased mobility and travel. Between January and May this year there have been more than 1,200 monkeypox cases in the Congo. There then occurred an overflow from Central to Western Africa, but while in Central Africa the disease was lethal in 5 to 10 percent of the cases, in West Africa it was less so, in around 1 percent. This can be attributed to the fact that the population in West Africa lived in cities, was wealthier, and had better healthcare treatment than that in Central African villages.

What is the incubation period and common symptoms?

The incubation period, from catching the virus to showing symptoms, is between 5-21 days, during which a person is asymptomatic and non-contagious. The person becomes contagious only as soon as symptoms develop, unlike with COVID-19 where one could transmit the virus two to three days before the onset of symptoms. This makes it easy to identify someone infected with monkeypox.

Symptoms start with fever, headaches, myalgia (body aches) and – unlike smallpox – swollen lymph glands. Within two to three days, a rash develops initially as small red macules, which swell up with fluid, then pus. The fever can persist for two to three weeks. During that time, it is important that the person should be well fed and hydrated. Whereas classical smallpox posed a danger to the nervous central system and the onset of variola encephalitis or variola pneumonia, monkeypox does not seem that severe.

How can it be detected?

For the time being there are no standard tests. We have the serology which has to be sent to the WHO for analysis, but that can only be conducted two weeks after initial symptoms appear. There is a PCR test, which we have already ordered and should be receiving at our medical centers within two weeks. The PCR can detect the virus immediately and can be done both from respiratory secretions and pustules.

Are we looking at another pandemic?

I don’t think so. A monkeypox vaccine already exists, it just needs to be produced in large amounts. But because of risks of toxicity, it may not be used on a large scale but only for those at high risk, which will help prevent a pandemic.

It is also important to note that the monkeypox virus is a DNA and not an RNA virus, like HIV, influenza, and SARS-CoV-2. It is a very stable virus that cannot mutate easily.

It is transmitted by contact with pustules, respiratory secretions, droplets, close contact through skin lesions, and sexual contact. If one is at risk of exposure to the virus, one should take the same precautions as those for COVID-19, namely masking, physical distancing, and good hygiene. Keep in mind that scabs from the pustules, too, can be contagious.

Unlike COVID-19, the monkeypox virus is not airborne; it does not require negative pressure; and will not place the world under lockdown.

Can you tell us more about the vaccine?

The existing JYNNEOS vaccine for smallpox has been licensed for use against monkeypox. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019 and by the European Medicines Agency in 2013. It is administered in two doses and is currently the only available vaccine for civilian use. It was modified and updated in 2021 and is now marketed under the names Imvamune or Imvanex.

People over 50 who received the smallpox vaccine before the 70s will be somewhat protected against monkeypox, keeping in mind that they are now older, and immunity tends to wane over time.