The Lebanese Government’s Financial Recovery Plan Explained

LAU hosts Deputy Prime Minister Saade Chami for a timely interactive discussion on the economic recovery program that aims to resolve, rather than manage, Lebanon’s financial crisis.

In an attempt to shed some light on Lebanon’s ongoing negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to tackle the country’s financial and socioeconomic meltdown, LAU’s Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution (ISJCR), in partnership with LIFE Lebanon and the Middle East Institute (MEI), hosted an interactive fireside chat with the Lebanese Deputy Prime Minister Saade Chami who is leading the Lebanese negotiating team.

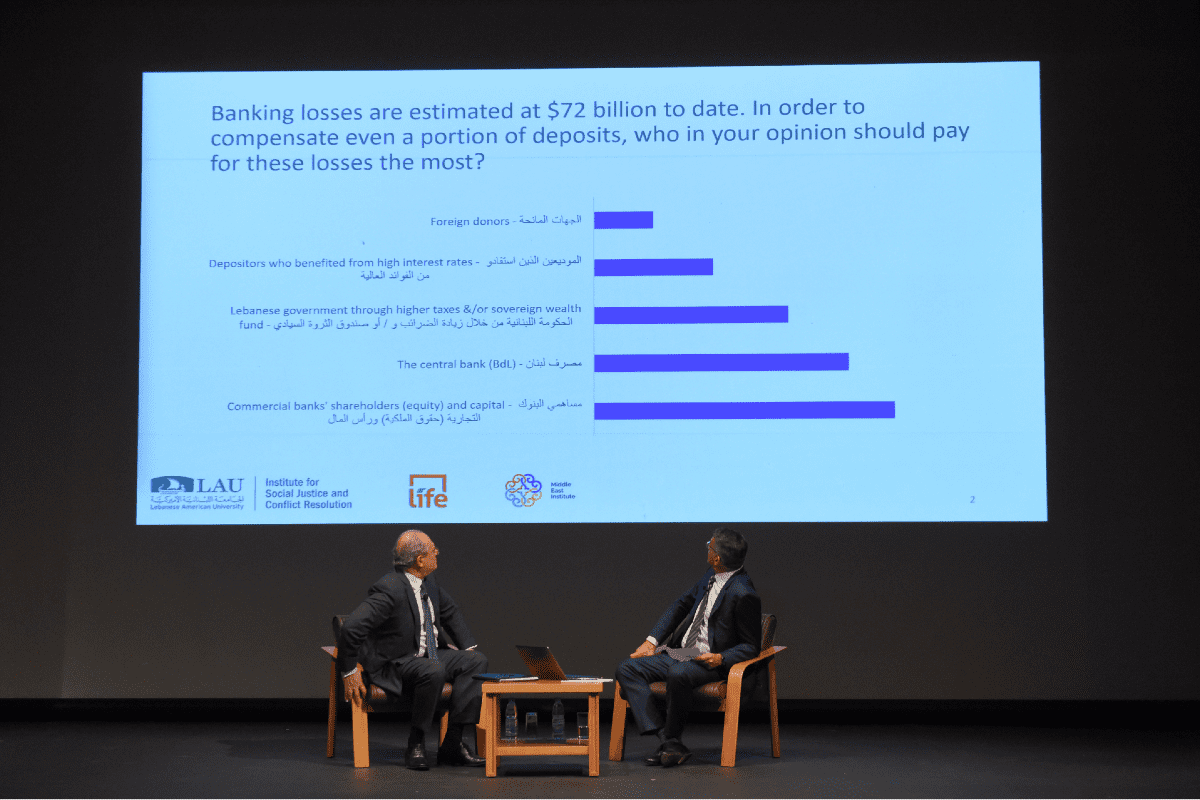

The two-hour event, held on July 13 on Beirut campus, was an opportunity for the general public to get some clarity on recent developments in the negotiations and voice their concerns. The discussion was driven by questions from online participants, interactive polls, and a Q&A that reflected public sentiment on core social, financial and economic issues.

In a candid and open conversation moderated by World Bank advisor Ronnie Hammad, Chami detailed the pending hurdles and the steps needed to resolve – rather than perpetually manage – Lebanon’s debilitating crisis.

“Every single person in this room, and following online, has been impacted one way or another by the ongoing economic meltdown,” noted Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs and ISJCR Director Fadi Nicholas Nassar in his opening remarks. The discussion, he added, fell in line with the institute’s and LAU’s shared vision of “fostering a space that brings together decision makers, academics and the broader public, while encouraging meaningful—even if critical—dialogue on national policy issues.”

Since the recovery plan was never fully communicated to the public, the purpose of the event, stated Hammad, was to “have a collective understanding of the problem that we are facing, get some details about the recovery plan, and understand the implications of the plan on the vulnerable and what it may mean for us.”

Fielding questions as they were received online, Chami addressed issues that have mystified the Lebanese, from the sudden onset of the economic crisis – a crisis, which, he clarified, had actually been simmering since 2011 but was managed with financial engineering to buy time – to the measures needed for recovery, and whether there was any hope of redressing the situation with some compensation to depositors.

Ensuring macroeconomic stability, he explained in response to one question, was a prerequisite to economic stability, and should be implemented regardless of the negotiations with the IMF. This entails fighting corruption in governance, reducing poverty, unifying the Dollar-to-Lebanese Pound exchange rate, reaching fiscal sustainability to reduce debt, and conducting state-owned enterprise reforms, starting with the notorious power sector.

Here, he added, time was of the essence, as the country’s deficiency currently stood at $72 billion, having risen from an estimated $69 billion in October 2021.

On the suggestion of using state assets to pay off bank depositors, Chami clarified that “Lebanon’s assets, such as gold, should be off the table, as we cannot deprive the budget of these resources – which ultimately are shared with future generations – to compensate a few thousand depositors.” Even if we were to consider this option, the value of the state assets, as it currently stands, “would require 60 years to plug the gap in the financial system.”

Nor can we count on oil and gas revenues, he stated, as “at the moment, we do not have full clarity over the value of Lebanon’s oil and gas, and whether it even exists. It is out of the question.”

So, who should bear the brunt of the bank losses?

Chami called for “respecting the hierarchy of claims,” which starts with looking into the commercial banks’ capital. Based on the internationally acknowledged Bank Resolution Law, he said, existing shareholders and some of the depositors can take part in securing recapitalization for the banks. Ultimately, this will decide the fate of the banks – whether they will survive, merge with other banks or cease to exist.

Diplomats, bankers, business owners, risk strategists, academics and students in attendance probed Chami on the role of the government in managing the crisis, and raised a number of points such as accountability, regaining confidence in public institutions and the banks, and the likelihood of economic growth, among other topics.

Positive developments, such as moving in the direction of lifting banking secrecy, would pave the way to transparency and accountability, he explained. In this regard, a forensic audit of the Central Bank could set a precedent for auditing other governmental institutions.

To questions regarding the impact of capital controls on economic growth and the insufficiency of IMF funds to cover the shortfall, he explained that fresh money was not subject to capital controls and that the IMF deal is not meant to make up for the deficit but to inspire confidence in foreign investments.

“A deal with the IMF is key,” he contended, which is why it was developed with the collaboration of multiple stakeholders, including bankers, labor union representatives, financiers and economists.

“We are hoping that the political establishment understands the severity of the economic situation, and accepts the reforms in parliament,” added Chami, acknowledging the persistence of public mistrust in the government – “an expected result of years-long economic mismanagement and misguided policies.” That said, he was adamant that there was hope for a deal with the IMF, citing “no major objection by any of the political parties.”

“The country can be put on the right path in a matter of a few months,” he reiterated, confident that once the needed reforms are met, “we can begin to get us out of the crisis within five years.”