Arabic Beyond Borders and Classroom Walls

Challenges aside, international students commit to a summer of Arabic learning and opportunity.

Despite security concerns, international students from Europe and the US determined to make the most of their summer signed up for four weeks of intensive Arabic learning at LAU, explored unfamiliar landmarks, and honored their Lebanese heritage.

The SINARC Arabic Language and Cultural Program offered through LAU’s International Services and Programs (ISP) has become a leading choice for Arabic language learners alike—international students, Arab expats, diplomats, dual nationals and business executives.

The multifaceted nature of the program—particularly the fact that it teaches both Modern Standard Arabic and the Levantine dialect—has helped it earn its stripes.

“I really like how the program mixes both formal and Lebanese colloquial Arabic,” said Hadi Noureddine, a Lebanese American studying at the University of Texas at Austin. “I feel that one cannot truly know Arabic without knowing both.”

For ISP Senior Director Dina Abdul Rahman, offering the unique Arabic program is imperative. “Bridging the gap between East and West and serving as a medium that connects cultures during highly divisive times,” she said, “is at the heart of LAU’s learning mission.”

This year, and for the first time ever, the program’s summer session was held in a hybrid model. Senior SINARC Associate Micheline Saadeh explained that she well understood why some may shy away from joining a program held in Lebanon given the security issues. On June 10, students opened their laptops instead of their suitcases for their first two weeks of synchronous sessions.

Even though learning went on behind screens at first, the connection that was created between language and culture was palpable. Yomna Chami, a SINARC instructor, feels that language and culture are one and the same and that “if you want to teach the language, you really need to teach the culture.”

To form this connection, Chami designed a slew of extra-scholastic activities meant to engage the students and have them learn Arabic in different settings. The activities ranged from simple tasks such as listening to songs and watching movies to those more complex like writing skits from scratch and performing them in front of the class.

For Chami, however, this was not enough, and culture “cannot only be found in textbooks and classrooms.” So, when the students landed in Lebanon for the second half of the course, and to really drive the point home, SINARC faculty made sure that they got the full Lebanon experience.

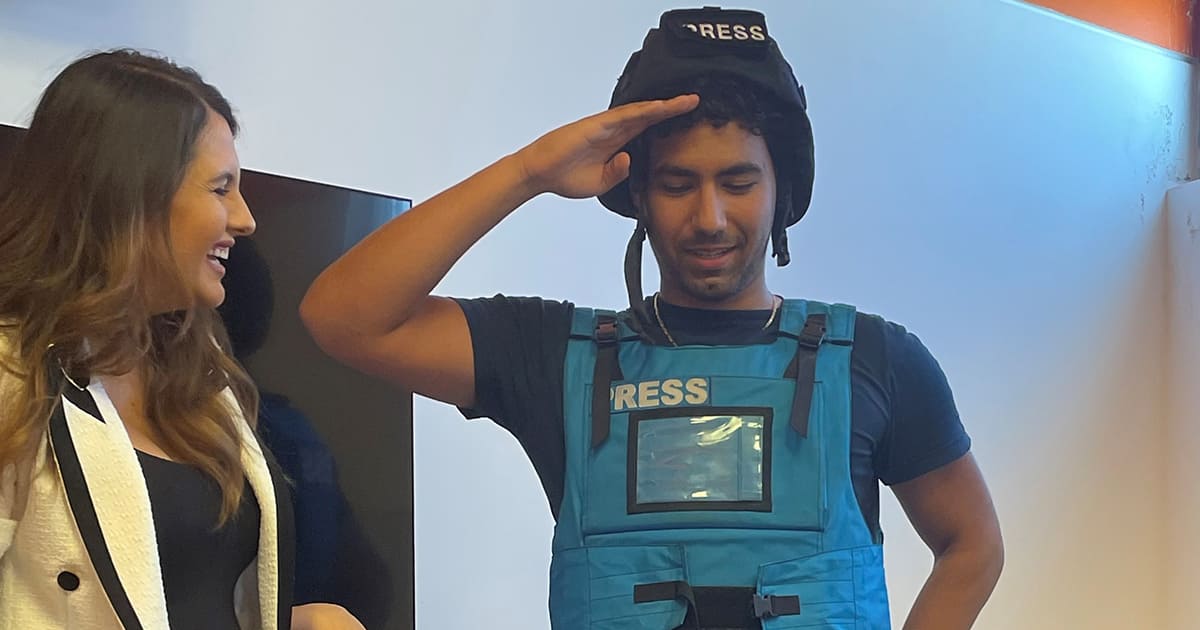

The program hosted local reporter Rima Hamdan who shared insights from the ground, having recently covered the war in South Lebanon, and fielded questions—in Arabic—from the students. Noureddine asked her about the difficulties of news reporting in formal Arabic, especially amidst civilian panic and distress. Edmond Farhat, another student studying economics in Italy, inquired about her first experience reporting in a war zone.

In a talk on Lebanese grottos and caves, Samer Amhaz, a caver and archaeologist representing L’Association Libanaise D’Etudes Spéléologiques (ALES), touched on the different types of grottos, preserving caves and safety measures while caving.

These events and cultural excursions, among which a field trip to the Cedar Nature Reserve and a virtual tour of the Mikhael Naimy Museum, stimulated the students’ understanding of the country and broadened their vocabulary in more specialized contexts.

“Whether it was tasting local food, walking through the Cedar forests of Bsharri, or learning Dabke from a professional, SINARC provided unforgettable experiences that cannot be found in a textbook,” said Noureddine.

The connection between language and culture was further solidified with the presence of a tutor—a third-year translation student with a strong command of both Arabic and English.

For Lucas Allam, a dual national Lebanese American studying history at Reed College, having a college student their age who was also very competent helped to familiarize them with what they learned in class. He added that the class size itself fostered a stronger sense of community, allowed for the teaching to be more focused, and made the entire process more collaborative.

“Though my first words were in Arabic I lost the language as I grew up in an English-speaking environment,” said Allam. “Regaining that helped me reconnect with a part of me that felt missing for a long time.”

The one sentiment that echoed through was that SINARC was an experience worth taking risks for; that with all the chaos and uncertainty, learning, once again, came first.

To sum it up neatly and in Allam’s words: “That my biggest frustration with the program was that it was too short is a good sign.”