Is AI a Tool or a Threat to Education? LAU Faculty Weigh In

LAU’s School of Arts and Sciences brought faculty and students together to explore how AI’s benefits and limitations affect education, from enhancing learning to raising ethical and academic concerns.

In today’s day and age, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has surpassed expectations, with critical discussions being held on how best to integrate it into teaching and learning.

In response to these conversations, LAU’s School of Arts and Sciences (SoAS) held a series of sessions between February 25 and March 6, titled Education Meets AI Seminar Series, that aimed to inspire new teaching strategies and provide actionable insights on AI’s increasing role in shaping education.

Engaging faculty and students from both the Beirut and Byblos campuses in the conversation, the primary focus of these discussions centered around understanding the potential, limitations and ethical implications of AI in academia, rather than imposing a fixed stance on whether it should be endorsed or rejected.

“Our aim with these sessions is to foster a culture of informed use and critical engagement when it comes to AI,” said SoAS Assistant Dean and Professor Sami Baroudi, who helped oversee each seminar with Associate Dean and Professor Sandra Rizk. “It is essential that we ensure that AI serves as an asset rather than a shortcut in higher education.”

Before introducing the three sessions and leading the series, Dr. Rizk raised a critical concern regarding whether “AI is the unexpected enemy.” She added that the sessions would evaluate its implementation at LAU and question if “it is harming or benefiting our students”.

The first session, presented by Associate Professor Mohamed K. Watfa, provided a comprehensive introduction of AI’s fundamental theories, core principles and the distinctions between AI-driven computing and traditional computational methods.

Dr. Watfa showcased the mechanisms by which AI is fundamentally changing how data is processed, analyzed, and utilized to make decisions in academia. He demonstrated how adaptive learning platforms rely on AI-driven technologies—such as neural networks, natural language processing and predictive analytics—to assess student progress and adjust instructional content accordingly.

“These intelligent tutoring systems,” he said, “are shifting the way we think about education. AI isn’t replacing teachers, but actually giving them better tools to support and engage students more effectively.”

Human oversight in AI-assisted education is a must, added Dr. Watfa, to ensure that AI tools are implemented in ways that support rather than undermine “the principles of academic integrity” as he phrased it.

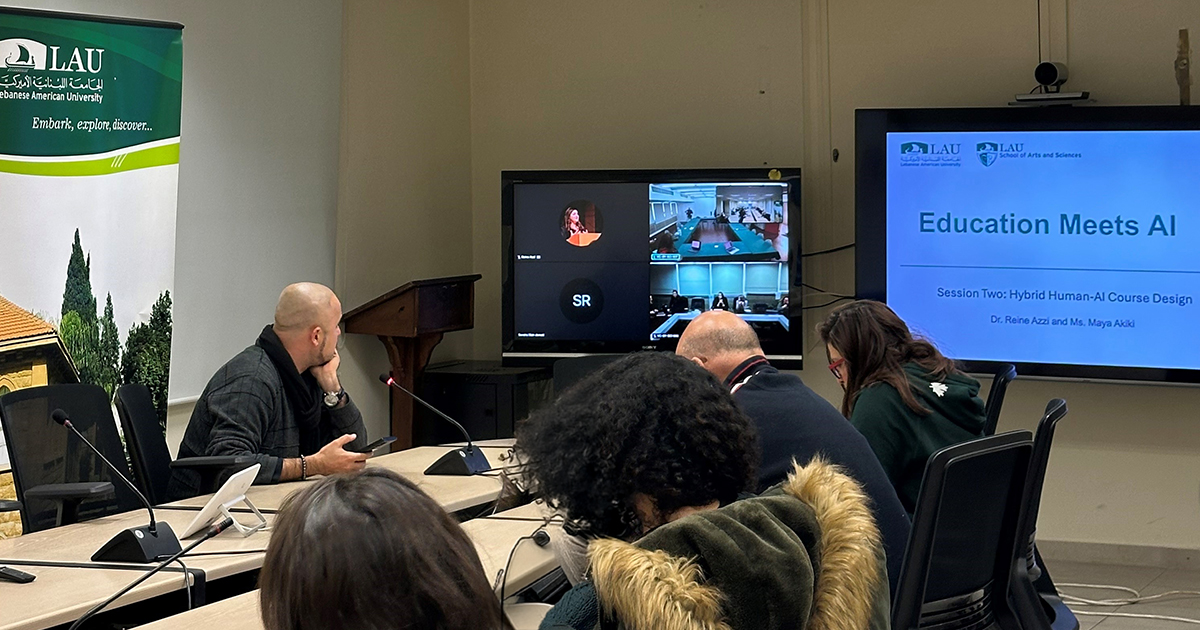

With the stage set for discussions on critically engaging with AI in academic and professional environments, the second session, presented by Lecturer Reine Azzi and Instructor and Writing Center Coordinator Maya Akiki, highlighted the challenges that accompany AI and its integration within course design through the lens of Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy—a classification of learning stages based on cognitive skills and learning behavior.

The session focused on the faculty’s concern about the increasing use of AI-generated work and the potential spread of misinformation as some students were submitting assignments that showed little critical engagement.

Dr. Azzi recounted instances where AI-generated citations led to fabricated references, and provided proactive measures to address the issue, such as requiring annotated bibliographies where students must justify their sources, along with integrating in-class writing assignments and conducting comparative analyses between AI-assisted and independently written work.

“These strategies are designed to help students understand that while AI can be a valuable research aid,” she said, “it should not replace independent thought and scholarly rigor.”

The session also tackled the AI Usability Spectrum, which categorizes AI tools based on their degree of involvement in the learning process. Akiki examined how AI can be incorporated at different stages of course development, from basic assistance—such as designing class activities—to more advanced applications, including AI-assisted research and analysis, to ensure that learning objectives are met without diminishing students’ efforts.

Once the skill is mastered, she added, “AI can become a partner or an assistive tool.”

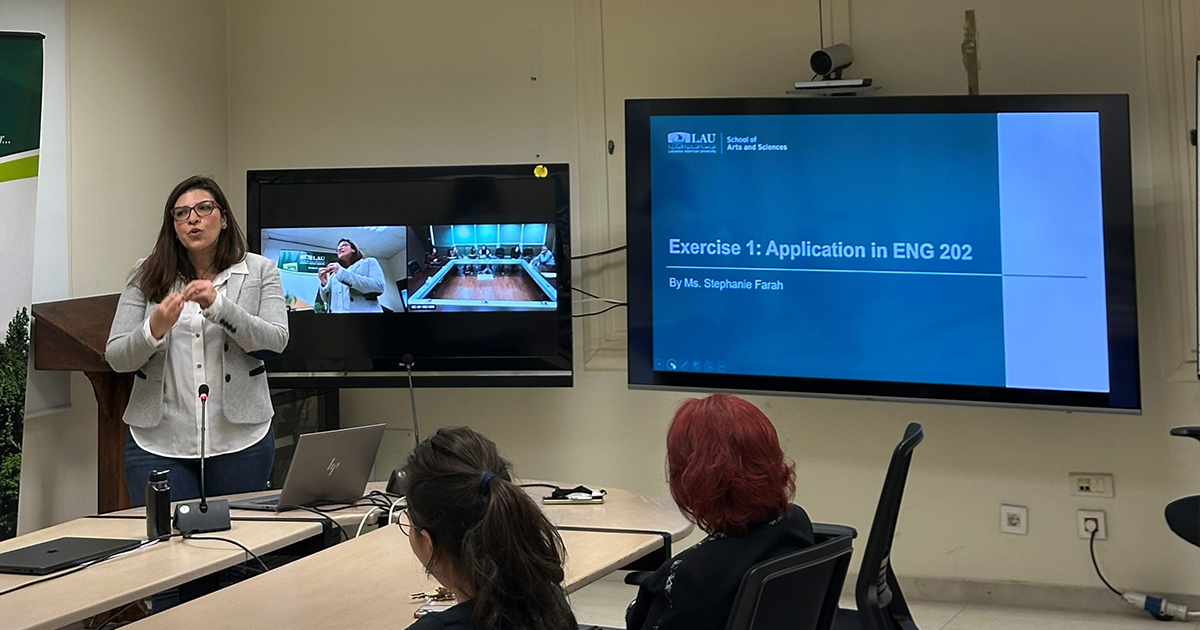

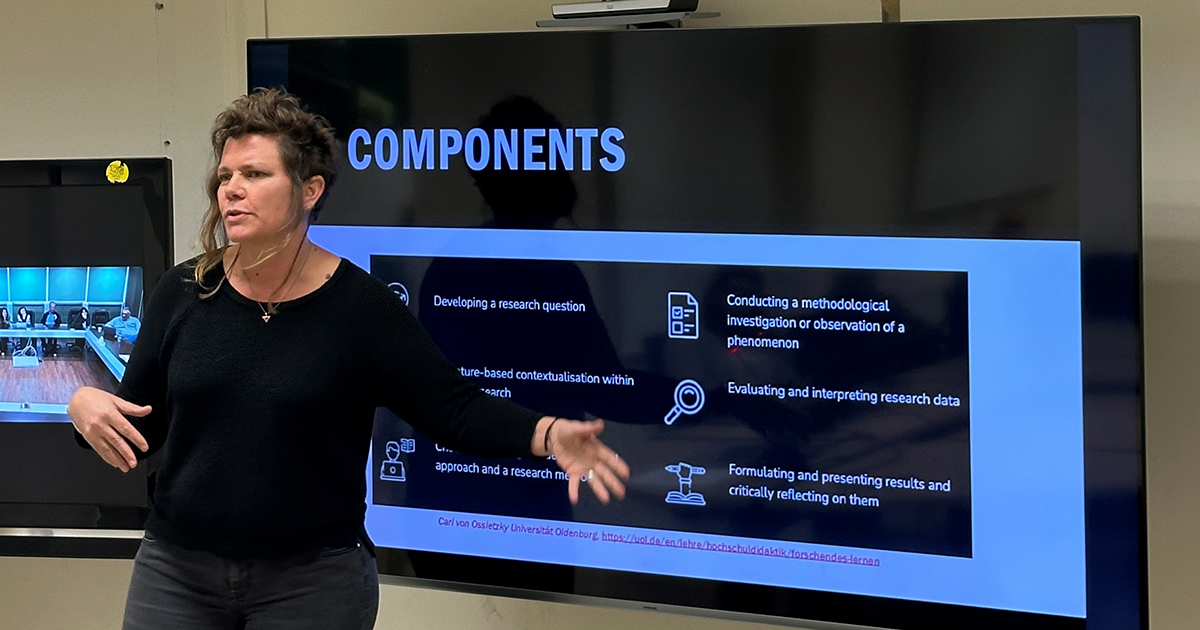

The third and final session, presented by Associate Professor and Chairperson of the Department of Communication, Mobility and Identity Gretchen King as well as Instructor Stephanie Farah, uncovered a pressing dimension of AI as a political tool by investigating its biases and the implications of AI-generated media narratives in perpetrating propaganda.

“In one of our courses,” noted Farah, “we had students compare AI-generated content with peer-reviewed sources, whereby they were encouraged to examine the limitations of AI in building arguments, spotting biases and making sure the information was accurate.”

Students initially wrote essays based on a Netflix documentary advocating for veganism, after which they used AI tools to expand their perspectives, only to find that AI simply mirrored their biases rather than offering counterarguments.

Following an in-depth analysis of scholarly articles on diet and nutrition, several students revised their initial positions. They realized the importance of fact-checking and relying on scientifically validated sources when conducting research.

The latter half of the session explored how AI-generated content reflects existing media biases and the extent to which it reinforces geopolitical power structures. Dr. King discussed the risk of AI legitimizing selective narratives instead of promoting objective or inclusive discourse.

“AI cannot be an objective or neutral tool because it is a product of the human-created systems that train it,” said Dr. King. “Rather than serving as a purely informational resource, it can perpetuate systemic narratives that marginalize certain perspectives while amplifying others.”

Dr. King added that by aligning with mainstream political discourses, AI not only omits crucial historical contexts but can also fabricate details that ultimately raise urgent questions about its authenticity in providing public knowledge.

Participants left the three sessions recognizing the need to critically assess AI to prevent it from becoming a tool for misinformation and enhance, rather than compromise, the principal goals of education.